The Congo’s role in creating the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was kept secret for decades, but the legacy of its involvement is still being felt today.

“The word Shinkolobwe fills me with grief and sorrow,” says Susan Williams, a historian at the UK Institute of Commonwealth Studies. “It’s not a happy word, it’s one I associate with terrible grief and suffering.”

Few people know what, or even where, Shinkolobwe is. But this small mine in the southern province of Katanga, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), played a part in one of the most violent and devastating events in history.

More than 7,500 miles away, on 6 August, bells will toll across Hiroshima, Japan, to mark 75 years since the atomic bomb fell on the city. Dignitaries and survivors will gather to remember those who died in the blast and resulting radioactive fallout. Thousands of lanterns carrying messages of peace will be set afloat on the Motoyasu River. Three days later, similar commemorations will be held in Nagasaki.

No such ceremony will take place in the DRC. Yet both nations are inextricably linked by the atomic bomb, the effects of which are still being felt to this day.

“When we talk about the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombing, we never talk about Shinkolobwe,” says Isaiah Mombilo, chair of the Congolese Civil Society of South Africa (CCSSA). “Part of the second world war has been forgotten and lost.”

The Shinkolobwe mine – named after a kind of boiled apple that would leave a burn if squeezed – was the source for nearly all of the uranium used in the Manhattan Project, culminating with the construction of the atomic bombs dropped on Japan in 1945.

But the story of the mine didn’t end with the bombs. Its contribution to the Little Boy and Fat Man has shaped the DRC’s ruinous political history and civil wars over the decades that followed. Even today the mine’s legacy can still be seen in the health of the communities who live near it.

“It’s an ongoing tragedy,” says Williams, who has examined the role of Shinkolobwe in her book Spies in the Congo. She believes there needs to be greater recognition of how the exploitation and desire to control the mine’s contents by Western powers played a role in the country’s troubles.

Mombilo too is campaigning to raise awareness of the role played by the Congo in deciding the outcome of World War Two, as well as the burden it still carries because of this. In 2016, the CCSSA’s Missing Link forum brought together activists, historians, analysts, and children of those affected by the atomic bomb, both from Japan and from the DR Congo. “We are planning to bring back the history of Shinkolobwe, so we can make the world know,” says Mombilo.

Out of Africa

The story of Shinkolobwe began when a rich seam of uranium was discovered there in 1915, while the Congo was under colonial rule by Belgium. There was little demand for uranium back then: its mineral form is known as pitchblende, from a German phrase describing it as a worthless rock. Instead, the land was mined by the Belgian company Union Minière for its traces of radium, a valuable element that had been recently isolated by Marie and Pierre Curie.

In no other mine could you see a purer concentration of uranium. Nothing like it has ever been found – Tom Zoellner

It was only when nuclear fission was discovered in 1938 that the potential of uranium became apparent. After hearing about the discovery, Albert Einstein immediately wrote to US president Franklin D Roosevelt, advising him that the element could be used to generate a colossal amount of energy – even to construct powerful bombs. In 1942, US military strategists decided to buy as much uranium as they could to pursue what became known as the Manhattan Project. And while mines existed in Colorado and Canada, nowhere in the world had as much uranium as the Congo.

“The geology of Shinkolobwe is described as a freak of nature,” says Tom Zoellner, who visited Shinkolobwe in the course of writing Uranium – War, Energy, and the Rock that Shaped the World. “In no other mine could you see a purer concentration of uranium. Nothing like it has ever been found.”

Mines in the US and Canada were considered a “good” prospect if they could yield ore with 0.03% uranium. At Shinkolobwe, ores typically yielded 65% uranium. The waste pile of rock deemed too poor quality to bother processing, known as tailings, contained 20% uranium.

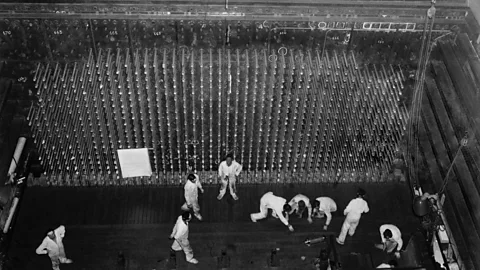

In a deal with Union Minière – negotiated by the British, who owned a 30% interest in the company – the US secured 1,200 tonnes of Congolese uranium, which was stockpiled on Staten Island, US, and an additional 3,000 tonnes that was stored above ground at the mine in Shinkolobwe. But it was not enough. US Army engineers were dispatched to drain the mine, which had fallen into disuse, and bring it back into production.

Under Belgian rule, Congolese workers toiled day and night in the open pit, sending hundreds of tonnes of uranium ore to the US every month. “Shinkolobwe decided who would be the next leader of the world,” says Mombilo. “Everything started there.”

All of this was carried out under a blanket of secrecy, so as not to alert Axis powers about the existence of the Manhattan Project. Shinkolobwe was erased from maps, and spies sent to the region to sow deliberate disinformation about what was taking place there. Uranium was referred to as “gems”, or simply “raw material”. The word Shinkolobwe was never to be uttered.

This secrecy was maintained long after the end of the war. “Efforts were made to give the message that the uranium came from Canada, as a way of deflecting attention away from the Congo,” says Williams. The effort was so thorough, she says, that the belief the atomic bombs were built with Canadian uranium persists to this day. Although some of the uranium came from Bear Lake in Canada – about 907 tonnes (1,000 tons) are thought to have been supplied by the Eldorado mining company – and a mine in Colorado, the majority came from the Congo. Some of the uranium from the Congo was also refined in Canada before being shipped to the US.

Western powers wanted to ensure that any government presiding over Shinkolobwe remained friendly to their interests

After the war, however, Shinkolobwe emerged as a proxy ground in the Cold War. Improved enrichment techniques made Western powers less dependent on the uranium at Shinkolobwe. But in order to curtail other nations’ nuclear ambitions, the mine had to be controlled. “Even though the US did not need the uranium at Shinkolobwe, it didn’t want the Soviet Union to get access to the mine,” explains Williams.

When the Congo gained independence from Belgium in 1960, the mine was closed and the entrance filled with concrete. But Western powers wanted to ensure that any government presiding over Shinkolobwe remained friendly to their interests.

“Since there has been a need for uranium, the US and the powerful countries have made sure nobody can touch the Congo,” says Mombilo. “Whoever wanted to lead the Congo had to be under their control.”

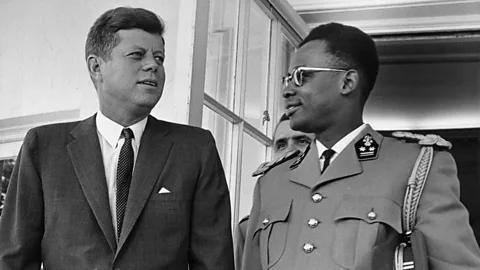

So important was stopping the Communist threat, says Zoellner, that these powers were willing to help depose the democratically elected government of Patrice Lumumba and install the dictator Mobutu Sese Seko in 1965 for a decades-long reign of ruinous plutocracy.

Attempts by the Congolese people to negotiate better conditions for themselves were attacked as Communist-fuelled sedition. “The idealism, hope, and vision of the Congolese for a Congo free of occupation by an external power was devastated by the military and political interests of the Western powers,” says Williams.

A wound unhealed

Mobutu was eventually toppled in 1997, but the spectre of Shinkolobwe continues to haunt the DRC. Drawn by rich deposits of copper and cobalt, Congolese miners began digging informally at the site, working around the sealed mineshafts. By the end of the century, an estimated 15,000 miners and their families were present at Shinkolobwe, operating clandestine pits with no protection against the radioactive ore.

Accidents were commonplace: in 2004, eight miners were killed and more than a dozen injured when a passage collapsed. Fears that uranium was being smuggled from the site to terrorist groups or hostile states vexed Western nations, leading the Congolese army to raze the miners’ village that same year.

Stories abound of children born in the area with physical deformations, but few if any medical records are kept

Despite the mineral wealth present at Shinkolobwe, since Union Minière withdrew in the early 1960s there has never been an industrial mine that could safely and efficiently extract the ores and return the proceeds to the Congolese people. After the Fukushima nuclear accident in 2011, any interest in extracting the uranium for civilian use withered away. “Uranium, even in its natural condition, resists control,” says Zoellner. “Right now Shinkolobwe exists in a limbo, a symbol for the inherent geopolitical instability of uranium.”

The ongoing secrecy around Shinkolobwe (many official US, British and Belgian records on the subject are still classified) has stymied efforts to recognise the Congolese contribution to the Allied victory, as well as hampering investigation into the environmental and health impacts of the mine.

This, says Williams, ought to be viewed as part of a long history of exploitation of the Congo by foreign powers, first by colonial occupation and then neoimperialism: “Not only did the Congo suffer so much during World War Two – forced labour was used for uranium mining, as it was for rubber and cobalt – but also the financial rewards for the uranium from the mine went to the shareholders of Union Minière, not to the Congolese.”

“The effects are medical, political, economic, so many things,” says Mombilo. “We’re not able to know the negative effects of radiation because of this secrecy.” Stories abound of children born in the area with physical deformations, but few if any medical records are kept. “I had a witness who died with his brain coming out of his head, because of the radiation,” says Mombilo. “In all these years, there is not even a special hospital, there is no scientific study or treatment.”

Many of those affected by Shinkolobwe are now campaigning for recognition and reparation, but knowing who should receive them – and who should pay – is compounded by the lack of information made available about the mine and what took place there.

“Shinkolobwe is a curse on the Congo,” says Mombilo.

But he adds that for over a century, the country’s rich resources have made possible one global revolution after another: rubber for tyres made automobiles possible, uranium fuelled nuclear reactors, coltan built the computers of the information age, and cobalt powers the batteries of mobile phones and electric vehicles.

“Our world is moved by the minerals of the Congo,” says Mombilo. “The positive thing I can say is that in all these advanced technologies, you’re talking about the Congo.”

The Congo’s impact on the world has been immeasurable. Recognising the name Shinkolobwe alongside Hiroshima and Nagasaki should be the first step to repaying that debt. {read}